HENRICO COUNTY, Va. — A decades-long mystery at Woodland Cemetery in Henrico has finally been solved with the discovery of Leslie Garland Bolling's grave, an artist with Richmond roots whose work graces some of America's most prestigious museums.

Woodland Cemetery in the East End is the final stop for generations of prominent African Americans who left their mark in another era.

Woodland’s executive director John Mitchell said, “We want to tell the stories of the people here. This is the connective tissue to Richmond. Woodland Cemetery is a Haven. A Haven for history.”

But a chapter of history and one grave of an accomplished artist from Virginia has been lost at Woodland Cemetery for decades.

Henrico County History Specialist and Woodland volunteer Mark Shubert has been searching for Mr. Bolling across the sprawling 33 acres.

“We weren’t sure if he was here," Shubert said. "We had probed this plot many times. We just never found his headstone."

Leslie Garland Bolling, who died in 1955, carved himself a lasting legacy.

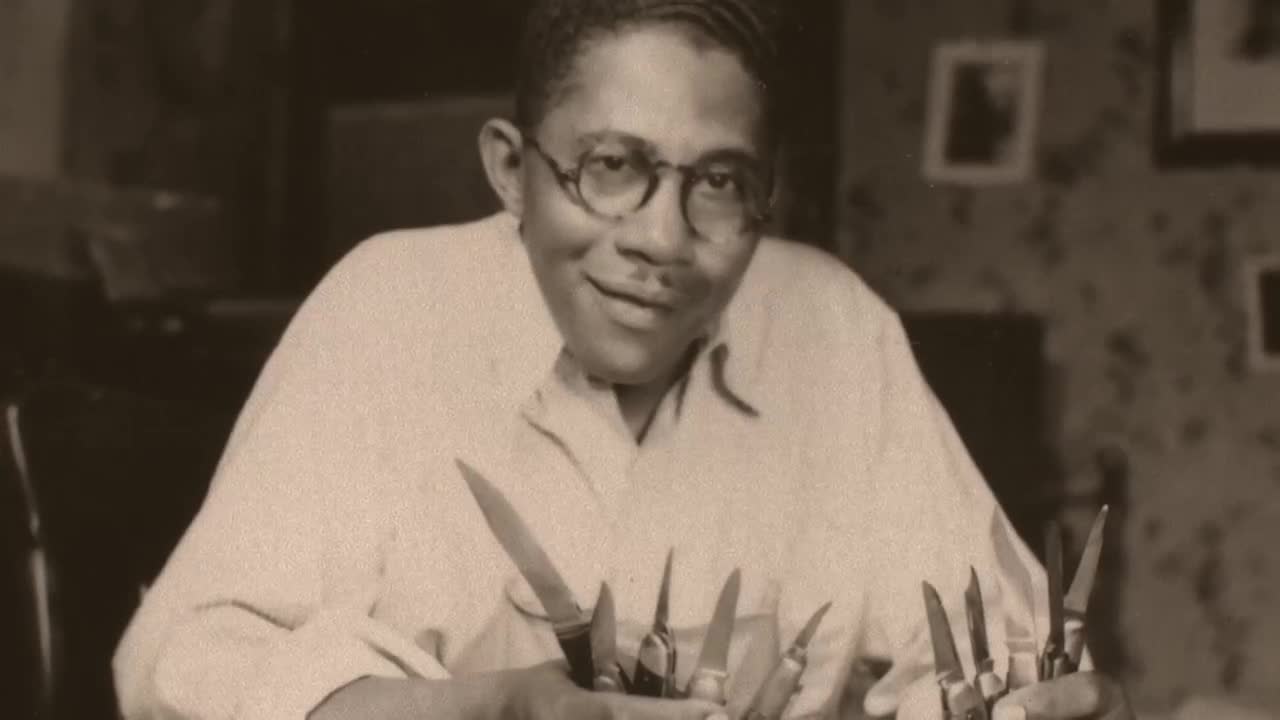

“He had a scroll saw and device and pocket knives. That is all he worked with,” said Shubert. “He was driven by what inspired him at that time.”

Surry County native Leslie Garland Bolling lived in Jackson Ward in the 1920s and 30s. When he wasn’t working as a porter or letter carrier, Bolling’s hands-on hobby filled his spare time.

“It is very important to know his story and know how he ended up being buried here,” said John Mitchell. “The beauty of his art is realizing his humanity. The same humanity as van Gogh.”

The largely self-taught sculptor, who attended Virginia Union University, found his subjects living next door.

“If you look at some of his carvings, he really wanted to show people from Richmond,” said Mitchell. “The African-American experience, what was going on back then."

With a block of wood, Bolling carved individuals often overlooked during the era of Jim Crow.

“They depict that life in Jackson Ward. That vibrant Harlem of the South and Black Wall Street. The day-to-day lives of the people that live there,” Shubert said.

Bolling’s sculptures of a cobbler, cook and washwoman caught the attention of art critics.

Barbara Batson, who literally wrote the book on Bolling, said the artist enjoyed national attention all while staying grounded.

“He exhibited his works in the 30s and 40s through the Harmon foundation, which was established to raise the profile of artists of color,” said Batson. “When you look at his work and you think about how he crafted, it you have to look at his intellectual approach to his art. I think it is remarkable what he did.”

In 1935, the Richmond Academy of Arts featured Bolling’s work in a one-man exhibit. It was a first for a Black person in Virginia.

Christina Vida with The Valentine History Center said Bolling’s Working Hand is a treasured part of their trove.

“You do not need to be from Richmond to appreciate Bolling‘s artwork. It has that spark of life,” said Vida. “You can see the cuticle on his hand. You can see the veins and folds of skin of the knuckles.”

Scholars know of at least 80 Bolling sculptures, but the whereabouts of more than half remains unknown. Some are privately owned while others belong to the Art Institute of Chicago and The Met in New York.

“We are so thrilled to be able to have these in these public collections and share them with the Richmond public,” said Vida.

Christopher Oliver, associate curator at the VMFA, said visitors can study two of six Bollings from the Museum’s collection now on display.

“I would say he perhaps is the most significant artist working in Richmond in the 1930s,” said Oliver. “Bolling is here. You can see his presence in these sculptures. So directly, I can imagine him holding these works in one hand and just working with the other.”

While Bolling’s pieces stand only about a foot tall, Oliver said what they represent is monumental.

“So, I think there is an interest on the part of art historians and the public to see how art was blossoming in this very difficult time during the great depression, particularly in these African American communities,” said Oliver.

Back at Woodland Cemetery, Mark Shubert’s long search for Leslie Garland Bolling hits pay dirt.

“I got the itch and said I’m going to find this headstone. Let’s put this mystery to bed,” said Shubert. “It was a good foot-and-a-half down. We found the flat headstone and felt some letters. Pour some water on the gravestone and saw the last name Bolling.”

In Section T, the curious history buff unearths two stones marking Bolling’s final resting place.

“Seeing that for the first time, it gave me chills. Just chills,” said Shubert. “It takes you on a little journey.”

71 years after his death, the accomplished craftsman is being discovered once again.

“He is an American artist. He represents the best of America,” said John Mitchell. “So when you see that it needs to be celebrated. He’s buried right here, and his story is out there to be found.”

Leslie Garland Bolling, the sculptor who whittled his way into the most prestigious museums across the United States, all while carving a spot into the heart of his hometown.

Watch Greg McQuade's stories on CBS 6 and WTVR.com. If you know someone Greg should profile, email him at greg.mcquade@wtvr.com.

📲: CONNECT WITH US

Blue Sky | Facebook | Instagram | X | Threads | TikTok | YouTube