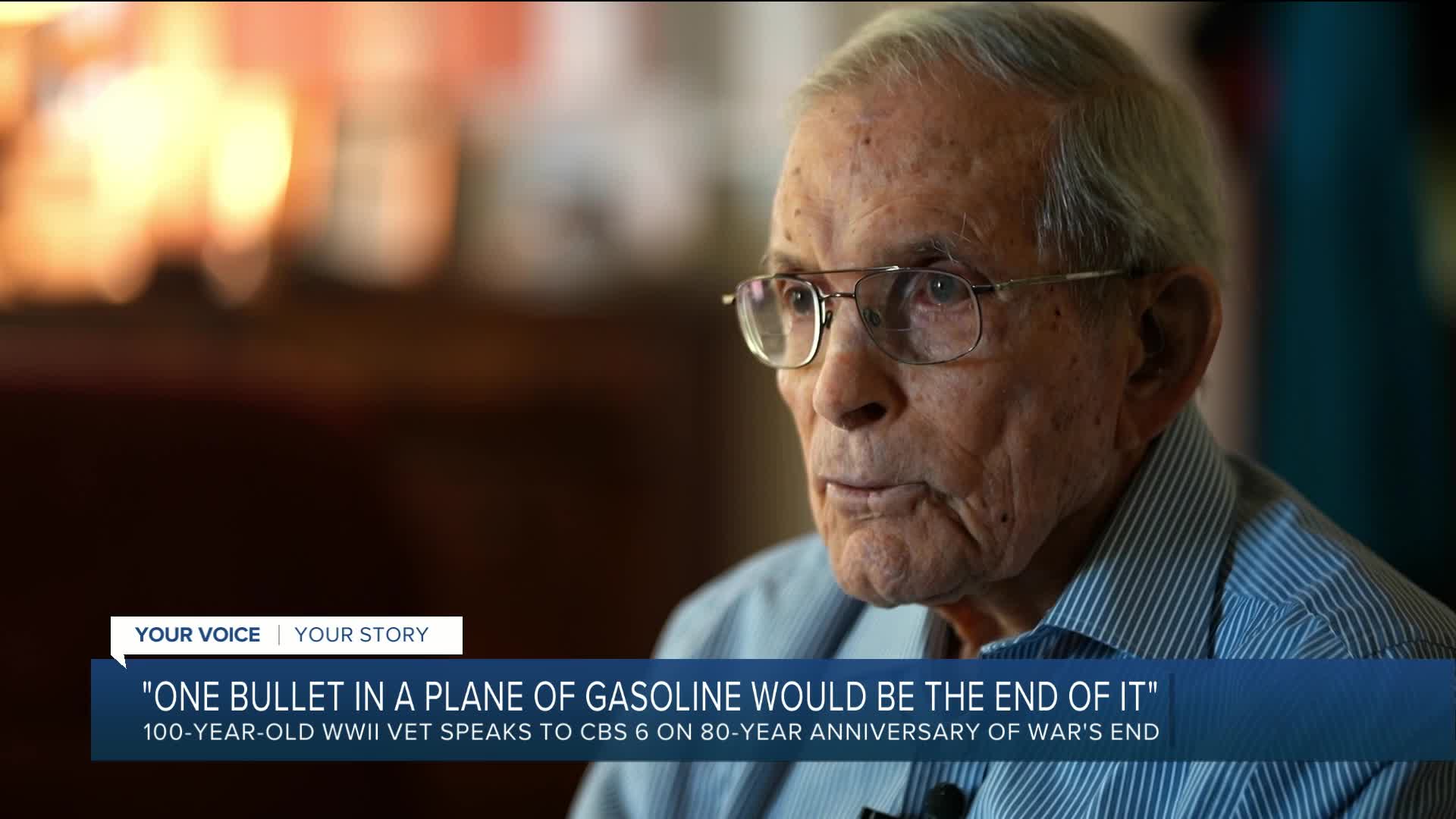

STONY CREEK, Va. — For a Sussex County farm boy used to doing his part, being drafted in 1943 was not something to make a fuss about.

"Everything was a new experience," said David Poole. "Nobody was all 'poor me,' and none of that kind of stuff. We were all eager."

The Army trained 18-year-old Poole as an airplane mechanic. He soon found himself on the cusp of history.

"We moved from England to Europe as the war progressed and we kept moving," Poole said. "We were mobile. We lived in tents. And that old airplane could fly on any kind of runway, even a short one. So as the war moved, we moved and ended up in Germany."

By the spring of 1944, Poole said every soldier in the European theater was aware something big was coming: an Allied invasion.

Still, he said, the crew chief had little time to ponder the historic moment. His focus: keeping his C-47 transport plane in the air.

"Everybody knew what it was, so that wasn't any secret, but most of the other stuff for me as the crew chief, it was my responsibility to refuel the plane," said Poole.

"Now D-Day was different. Everybody knew what D-Day constituted, what it amounted to, and your part in it was just whatever it was. You drop troops, or you pull gliders, and the next day you drop supplies, or you haul gasoline up behind the lines."

Poole says 'duty' was a reflex back then and that meant absolute faith in the mission.

"You never thought that you might not make it this time, or it might not be a successful invasion, or anything," he said. "We had no doubt that we were going to defeat Germany. I mean, that was just the mindset."

That mindset also kept Poole from worrying about what kind of target a plane packed with a fuel delivery might make.

"I never thought about one bullet in a plane of gasoline would be the end of it," said Poole. "The German Air Corps was just about decimated by time I was flying in '44, so we were fortunate that way."

"Did you take fire?" I asked.

"No. I heard it when I was close enough," Poole responded. "When we were laying up close behind the lines with a load of gasoline and in the process of unloading, you could hear the hear the fighting going on. I don't know how close it was, maybe a mile or so. But we never took fire. We just had the day's assignment. You took care of it and flew back home that night. And I was fortunate, just so fortunate, not to have to be in the hand-to-hand fighting."

But reminders of the war's toll were unavoidable even after the war, when bringing American prisoners of war back to England on gurneys.

"We could carry 18 people on a litter back to England," said Poole. "They were all in litters, our boys who had been prisoners of war. I didn't haul any of the German prisoners. That was a sort of a sad mission because some of them were in pretty bad shape. They weren't sitting, they were all on litters. They were happy on that flight because they were going home, but you could tell that they were starved to a certain extent. Some of them were just like skin and bones and had to go through some hospitalization."

But like so many of his generation, at war's end, the return to civilian life was immediate, and something like normal life resumed.

The GI Bill provided many with an opportunity to get a college degree, and for Poole, a chance to go back to a sport he excelled in.

"I played baseball at Virginia Tech with a degree of success, and our sophomore year, I needed money," Poole said. "I was living on $80 a month that the government sent me. And I was married, so I decided to sign a professional baseball contract. At that time, I didn't want to go with the Yankees, because they had Joe DiMaggio and several other outstanding outfielders, and I was already in my 20s, so I was looking for some team that needed help. So, I signed with the Chicago Cubs' farm system."

The dutiful farm boy eventually returned to his beloved Stony Creek, Virginia after 35 years with the power company that became Dominion Energy.

And looking back, what might Poole consider his biggest challenge?

"I told my wife and others that if I had stayed in professional ball, I would be dead by now," he said. "That's a tough life. What you eat, how you sleep. It always, it's tough."

The US Veteran's Administration estimates there are 66,000 living American veterans of World War II.

Watch: Henrico World War II veteran shares memories 80 years after war's end

CBS 6 is committed to sharing community voices on this important topic. Email your thoughts to the CBS 6 Newsroom.

📲: CONNECT WITH US

Blue Sky | Facebook | Instagram | X | Threads | TikTok | YouTube